Ingham written as ‘Hincham’ in the Domesday Book, means ‘seated in a meadow’. Nothing of this period survives in the church, the oldest part of which now seems the stretch of walling at the South West corner of the chancel.

This is made of whole flints, as against the knapped flint of the rest of the building, and contains traces of a blocked priests doorway.

In spite of the herringboning of some of the rows of flints, it is probably not older than the thirteenth century.

The rest of the body of the Church was rebuilt in the years leading up to 1360. Work would have started with the chancel, but it is uncertain when it was begun.

The tomb of Sir Oliver de Ingham, who died in 1343, is in the founders position on the north side of the chancel, and since the posture of the effigy is, as we shall see, already old fashioned for the date of death, it seems most likely that it was commissioned during his lifetime and that he rebuilt the chancel (which is Pevsner’s view), or that work began immediately after his death by his daughter Joan and her husband, Sir Miles Stapleton, who also rebuilt the nave. The Stevensons established a College of Friars of the Order of Holy Trinity and St Victor to serve Ingham, and also Walcott.

The friars were installed in 1360, and originally consisted of a prior, a sacrist, who also acted as vicar of the parish, and two more brethren. By the early sixteenth centaury there were six canons in addition to the prior and sacrist, but by 1536, when Sir Thomas Cromwell’s commissioners came to investigate it, they found that the friary had already ceased to function, and so did not need to be suppressed.

The main object of the Trinitarian was the redemption of captives, particularly those taken prisoner during the crusades, for which a third of their income was set aside, but by the time they came to Ingham; the crusading movement had already had its day. The order never became important in this country, and the Ingham priory, despite its modest size, became the motherhouse of the few other Trinitarian foundations in England.

Small remnants of the conventual buildings can be seen on the north side of the Church, and there are a few details of interest.

|

|

|

The largest fragment of the priory to survive forms the nucleus of the neighbouring Swan Inn.

Nearly all the window tracery of the church had to be renewed in Victorian times, but it actually represents accurately what was there before.

It reveals a typically Norfolk mid-fourteenth century alteration of decorated and perpendicular designs. The arcades are unaltered work of about 1360, with their tall quatrefoil piers with filleted diagonal shafts and moulded arches.

The first important addition to the fabric of 1360 was the south porch, built in 1440. It has tierceron-vaulted ground floor, and exceptionally, two rooms above. Only six other medieval porches of more than two storeys survive in the whole of Britain. At Ingham, the two upper storeys formed living quarters for the sacrist.

The first important addition to the fabric of 1360 was the south porch, built in 1440. It has tierceron-vaulted ground floor, and exceptionally, two rooms above. Only six other medieval porches of more than two storeys survive in the whole of Britain. At Ingham, the two upper storeys formed living quarters for the sacrist.

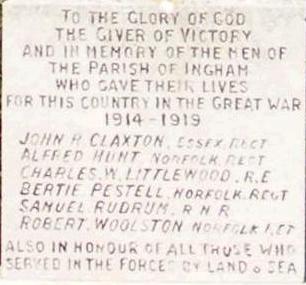

Near the porch stands the War Memorial.

|

|

|

| War Memorial | War Memorial in detail |

The tower was being built in 1488, for in that year Roger King, rector of the neighbouring parish of Sutton bequeathed 6s 8d towards it. It stands just over 100ft high, and it has stepped battlements, an East Anglian feature probably derived from churches in the far south of France seen by pilgrims en route to Compostela.

These battlements are decorated with the flint flush work, as are the buttresses and base of the tower. The battlement decoration includes on the east side, the Maltese cross of the Trinitarians, which can also be seen on the west doorway, along with arms of Ingham, Stapleton, de la Pole, and Felbrigg.

|

|

|

| Ingham Church Tower | Ingham Sound Hole |

The “sound holes”, another feature of Norfolk churches, have intricate tracery. In fact “sound holes” were probably designed to give light and air to the ringing chamber, for they are always on the floor below the belfry.

The bells are now rung from the ground floor. There are two, one medieval, inscribed “Ave Maria Gracia Plena Dominus Tecum”, and the other dated 1661, and inscribed “My treble is when I should sing St Andrew’s tenner spoil that ring”. By the early nineteenth century the church had fallen into serious disrepair.

The west window of the tower had been partially bricked up in 1779, and many others followed, while the east window was partly filled with clay. In 1833 a start was made on collecting funds for the major task of restoration, which was undertaken by J. P. Seddon and Ewan Christian and completed in 1876.

The damaged windows were repaired and reglazed, and the remaining glass from the east window was put in the clerestory openings, which gave welcome extra light in a church, which tended to dark owing to the virtual absence of windows on the north side where the conventual buildings abutted it.

Nave and chancel were re-roofed, and the sedilia practically rebuilt on the pattern of the largely original piscine which is part of the same composition. The medieval stalls were repaired, and the pitch pine pews were installed in the nave, though some of the old oak poppy-headed bench ends were retained.

The floor was retiled, and the choice of patterns is particularly pleasing. The new pulpit made of Caen stone, and the elaborate wooden eagle lectern was designed by Seddon. Finally, the children of the parish raised £60 – no mean feat considering money values at the time – for the font to be raised on its green and red marble columns on top of a stone platform.

Seddon’s and Christian’s work undoubtedly saved the church from ruin, and the fact that in spite of the extensive work that had to be done it still appears to be a medieval rather than a Victorian building is a tribute to their sensitivity.

One further piece of work suggested was not carried out. Seddon made designs for the restoration of the stone pulpitum, or screen, which divided the parochial nave from the Trinitarians’ chancel and of which only the base now remains. It was an ambitious and fanciful design, undoubtedly more elaborate than the original can have been, and it is difficult to know whether to be relieved or disappointed that it was not done. Mr Sid and Mr Fred Tillett, who was released for this work by Mr J. J. A. Kendall, then churchwarden, carried out further restoration work in 1969. At the same time, Rev David Ainsworth, Vicar of Northrepps, executed the painted shields in the roofs.

| The font, looking a little self-conscious as a result of its elevation in Victorian splendour, is a simple thirteenth century piece made of purbeck marble in a mass produced design, found in many parts of England, particularly in place within easy reach of waterborne transport. With their unadorned shallow blank arches these fonts look dull nowadays, but there is little doubt that they were originally painted with figures of saints orvirtues as a sort of cut-price version of some of the more elaborate fonts of the time, which had arcades containing carved figures. |  |

|

| Ingham Font |

There are several interesting tombs. In the nave lie Sir Roger de Bois and his wife Margaret. He died in 1300 and she in 1315, according to the now almost illegible inscription, but the costume details on their alabaster effigies suggest that their monument was not made until at least a generation later.

|

|

|

| Tomb of Sir Roger and Margaret de Bois | Artist's Impression of original tomb |

The monument is sadly mutilated. Socket can be seen for the iron railing, which originally surrounded it, and there are still traces of the colour decoration with which it was painted. Look especially at the little carvings of the resurrection on the west side of the tomb chest, and the underside of the cushions on which Margaret de Bois’s head rests.

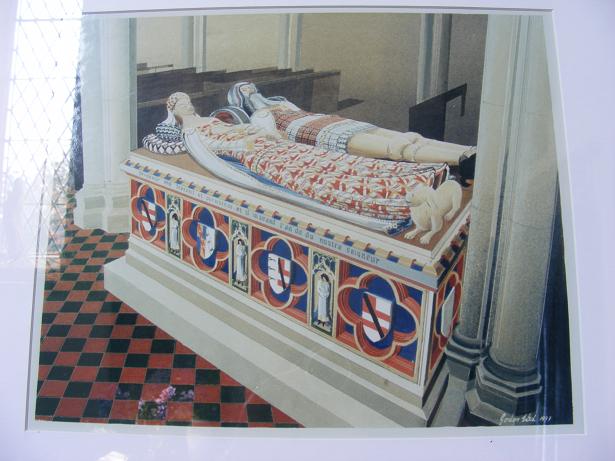

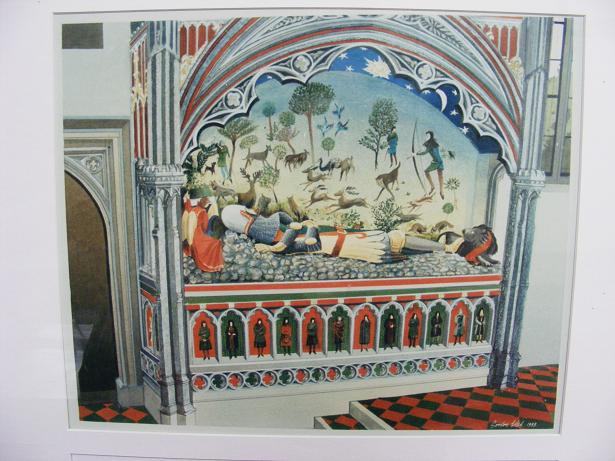

On the north side of the chancel lies Sir Oliver de Ingham, as we have already seen.

|

|

|

| Tomb of Sir Oliver de Ingham | Artist's Impression of the tomb |

The lively pose of the effigy came into fashion about 1290, but was being replaced by more reposeful figures by about the time Sir Oliver died in 1343.

Much more unusual is the bed of pebbles, an idea only found elsewhere at Burrough Green, near Newmarket, and in Reepham.

The Reepham tomb, commemorating Sir Roger de Kerdiston, who died in 1337, gives a good idea of what Sir Oliver’s tomb once looked like, for the elaborate framing arch, fragmentary at Ingham, is complete at Reepham.

Both tombs are said once to have had a painting of a hunting scene under the arch though these have now disappeared, but the close similarity of the two memorials makes it more or less certain the same man designed them. Fewer traces of colour remain than on the de Bois tomb, but enough to suggest a sumptuous finish worthy of the sculpture.

If both of these medieval monuments are sadly damaged, they have at least fared better than the rest. Several were so badly damaged that they were removed by Ewan Christian, and three outstanding brasses were stolen earlier when the church was neglected.

However, a rubbing taken in 1781 shows that Sir Miles Stapleton and his wife Joan were depicted hand in hand, one of the earliest memorials in Britain to use this attractive idea, and that once his name Jakke, a pet dog, was recorded at his masters feet. The other fragmentary brass is the one to Lady Elizabeth Calthorpe, whose only interesting detail is the assertion that she died on July 23rd 1536. There are a few early nineteenth century wall tablets, one, to Elizabeth Wymer, who died in 1842, signed by de Carle of Norwich.

|

|

|

| The Pulpit | The Sidechapel |

So much for a description of the church as it now is, but what of the people of times past? Here are some examples of those we know about.

First, perhaps, go back just over a century, and you can picture the Victorian workmen bringing the building back from near ruin. See the scaffolding busy with masons and carpenters, and John Seddon making sketches for this proposed reconstruction of the pulpitum. Picture the children’s delight when their efforts enabled the font to be raised to its proud setting, and Nathaniel Wilson, the vicar, watching his church come back to life and beauty before his eyes.

| Go back another hundred odd years, when the old brasses lay gleaming in the chancel, and the squire and his relations, dressed in the elaborate costume of Georgian gentry, dozed peacefully through the long sermons, while the humbler villages sat uncomfortably but respectfully on their hard benches. Another hundred or so years back in time, and the congregation is a puritan one. The holy table perhaps stands in the body of the chancel or nave, with seats all around it for the soberly dressed communicants. There is no sign, in their gravity and quiet piety, of the frenzy of destruction unleashed on the church not so long before, for the second time in a century, to rid it from anything that could possibly be considered idolatrous – glass smashed from the windows, whitewash over the wall painting and biblical texts in their place, wooden statues burned and stone ones hacked to pieces. |

|

|

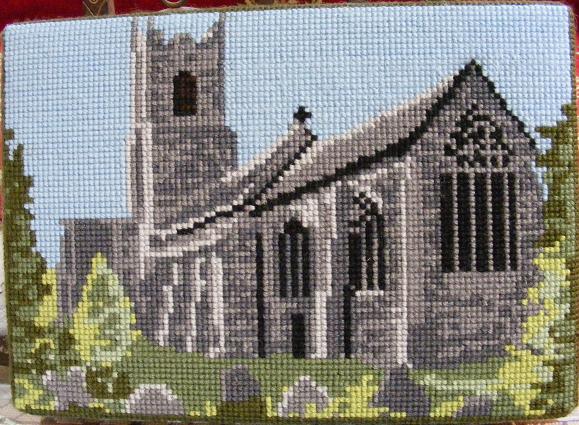

| Kneeler depicting Ingham Church |

|

Back now to the sixteenth century and the last day of the priory. See the brethren in their white robes bearing the Maltese cross in red and blue, filing in through the now blocked doorway for the last performance of the old choir offices. You will have to peer carefully, for the pulpitum was fairly solid, designed to give them a degree of privacy, but, if you cannot see them well, you can hear them in the regular rise and fall of the ageless plainsong melodies, and the sonority of the rolling Latin phrases. See them as the service comes to an end, walking out again through the north door into the conventual buildings, never, as friars, to return. |

|

| The decoration of the tower ceiling |

| A happier occasion in 1360, as Sir Miles and Lady Stapleton take part in the dedication of the priory they had endowed; he wearing the insignia of the Garter, of which he was one of the first recipients; she, no doubt, looking at the tomb of her father, Sir Oliver, splendid in its pristine state. Perhaps, if it was he who planned so fine a chancel, he and his wife had already had the idea of making the church collegiate. If so, their daughter would be proud that she and Sir Miles had been able to fulfil her parents’ wish. There they stand, in a church ablaze with colour – stained glass, painted walls and screen work, a glorious reredos behind the high alter. For even now after more than a century of loving care, the church is only a shadow of what it once was. |

|

|

| The Chancel |

Over twenty generations have worshipped in this place; more still have worshipped on this site. In turn they have brought with them their joys and their sorrows, their successes and their failures. They have come here to be married, to have their children baptised and confirmed, and to have their loved ones committed to the grave: all to this building and to the God whom they have found most easily here.

And people still come. A service is held every Sunday, and the church is open every day for visitors, perhaps looking at the tombs, the history, the architecture, but we hope also sensing the presence of God himself here and adding their prayers to the countless prayers of years gone by.

|

| The Altar |